Many visitors (myself included) are surprised on their first visit to Rebel State Commemorative Area. The site marks the grave of a lone Confederate soldier, but is also the site of the Louisiana Country Music museum.

The Country music museum is absolutely worth the drive. The museum offers a Louisiana-focused history of Country music, from its traditional folk roots to the 1970s. The story of the site is as compelling as it is troubling (see below for my thoughts on the troubling part).

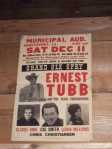

The mission of the site was not entirely clear; however, interpreting the history of country music through the Louisiana Country Music Museum and maintaining the historic site marker seem to be obvious points. We visited on a cold morning and didn’t encounter any other visitors. The site is a wonderful resource on Louisiana Country music, provides some interpretation of the Civil War, and offers picnic tables, barbeque pits, a pavilion, and a large amphitheater (unfortunately, the site no longer regularly hosts music). The interpretive ranger was helpful, knowledgeable, and full of new ideas, including building a recording studio on-site for area aspiring musicians.

The museum pays tribute to early gospel, folk, and work-song influences, and does a splendid job of interpreting the early recorded era of Country music genres, including the Louisiana Hayride, KWKH, and KRMD in Shreveport. The museum does not interpret recent trends in Country music, country pop, or most anything after the “Urban Cowboy” phase.

My main concerns with the museum were in presenting Country music’s multi-ethnic roots. While one display notes that the guitar was of Spanish origin (via Mexico) and another shows the dissemination of the (Irish) fiddle, there is no mention that the mandolin came from Italian immigrants or that dulcimers, accordions and other squeezeboxes are from Germany and Central Europe, or that the banjo comes from West Africa.

Much more troubling are the possible links between music and commemorations to the Confederate solider.

The Confederate solider was separated from his unit and supposedly killed by three Union cavalrymen, while stopping at a spring for a drink of cold water.

The Barnhill family buried the solider. A marker was placed on the grave in 1962, and annual memorial services grew to include live performances of Country music.

The narrative is telling, and parallels the narrative of southern defeat repeated for one hundred years: The federal government and northern industrialists, lacking any respect, gentlemen’s code, honor, or courtesy for the old ways of life, outnumbered and outresourced poor “Johnny Reb” and kicked him (them) while he (they) was (were) down. But a good family restored his (their own imagined) honor in death, and many people commemorate his (the lost cause’s) memory.

The early 1960s was the Centennial of the Civil War. The late 1950s and early 1960s also saw a resurgence of the Ku Klux Klan (after its brief post-war decline and infiltration by Stetson Kennedy) and a number of cases of local police and hate groups working together -essentially sanctioning state violence against Civil Rights groups. The early 60s also saw the killing of Megar Evars in Mississippi. It was in this context that the so-called “Confederate Flag” came into wide use throughout the South. The placement of this flag near the door to the museum is problematic. The flag, similar to the Flag of the Army of Northern Virginia (it is the Second Naval Jack, but colors of the Beauregard’s Battle flag), is often used as a symbol of racist hatred. The flag was placed on the statehouse in South Carolina in 1962; George Wallace flew it in Birmingham in defiance of Kennedy asking him to begin racial integration. A friend of the family told me the first time she saw them in numbers was the early 1960s. In race, amenities, and psychic income and elsewhere, Mwangi Kimenyi argues that the flag, “represents the mark of ‘old all-white’ traditions” and exclusionary feelings. The flag often acts as a marker saying “you are unwelcome.”

By the 1970s, the grave-site saw an annual memorial service “for the solider,” replete with live gospel and country music. The 1970s are noted as a time where racial-cultural war was fought with music. In Rock (a genre I am more familiar with), Neil Young indicted youth of the South with “Southern Man,” and Skynard responded to Young in “Sweet Home Alabama.”

Louisiana has the second highest proportion of Black folks in the United States. Natchitoches Parish has a higher percentage of people of African ancestry than the state average (about 38% Black), but the Marthaville area is outside the Red River Valley in an area of Anglo “white” farmers and their descendants. A place with those demographics seems obvious to commemorate country music. But rural transformation has affected Black and white families unevenly (see Southern Farmers and their Families by Walker, reviewed in Red River Valley Historical Journal 2007 (5) volume 5, 147-149), and in places where the slightest material advantages or “psychological wages” seem like clear class differentiation, racism manifests as “common sense” among working class whites.

Given this complex context, placing a “Confederate” Flag near the entrance to the museum invites accusations. The placement of this flag near the door to the museum is problematic.

The state would do well to 1.) highlight contributions of ethnic immigrants 2.) highlight contributions of African Americans to country music (not just Huddie Ledbetter) and explain the African origins of the banjo, 3.) place the Civil War interpretation in context and, 4.) offer an annual music festival that highlights both country and the breadth of folk musics of Louisiana.

Comments Off on Site visit: Rebel State Commemorative Area/ Louisiana Country Music Museum